Wir schaffen das diesmal - oder?

The Far Right AfD doubled its vote share to one in five in the February 23 Bundestagswahl - reaching out to many more younger voters and west Germans. Only economic reform can stop its progress.

The most extraordinary outcome of the German general election on February 23 in a way is the scale of voter turnout: 82.5%, up 6.1% on 2021 and the highest level seen since (re)unification in 1990 when it was 'just' 77.8%. In an era of voter distrust in politics and democracy across the West this testifies to a strong belief among Germans in the post-1945 political system. (In the 2024 US presidential vote turnout was 63.9% of eligible voters).

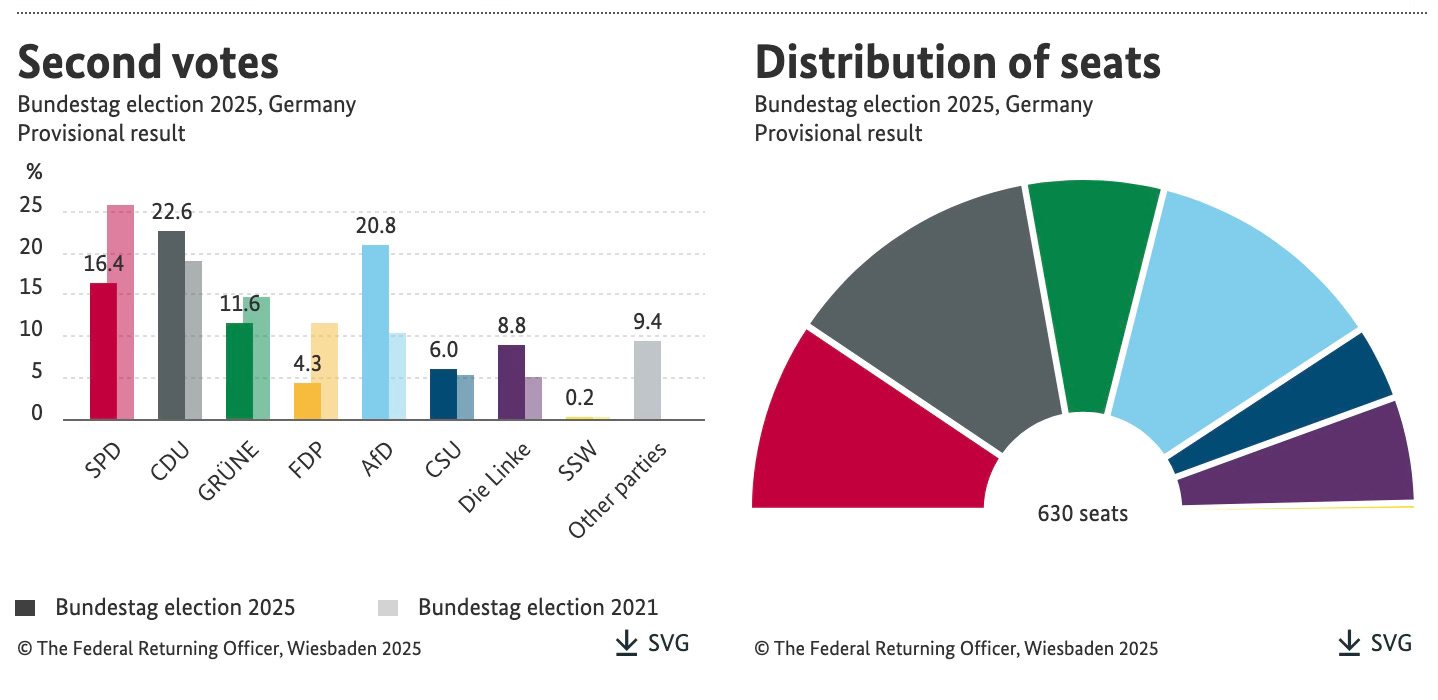

But there are worrisome trends even so. The overall result mirrored the prognosis of the opinion polls over the days and weeks before polling day: the CDU/CSU came first, the AfD second and the SPD third. That much was vorprogrammiert but Friedrich Merz's CDU and its Bavarian sister CSU won under 30% (28.5%), its second-lowest score in post-WW2 Germany and hardly a ringing endorsement (up 4.4% on 2021). The AfD doubled its own score on 2021 with 20.8% while the SPD slumped to its lowest score (16.4%) since March 1933 (18.3%) or 1887 (10.1%).

What is pretty shocking here is that together the Christian Democrats and Social Democrats polled just 44.9% or around half of what they polled in, say, 1980 (87.4%). The two great Volksparteien (big-tent parties) are definitively in the doldrums in an accelerating trend over the past couple of decades.

The far-right AfD, on the other hand, is clearly extending its reach from its base in eastern Germany (the old GDR) to the west: in the old industrial heartlands of North-Rhine Westphalia, for instance, it won 16.8% (second or regional list vote) to the SPD's 20% and the CDU's 30.1%. Even in Bremen where it came fourth it scored 15.2% and in prosperous Hamburg where it finished fifth 10.9%.

It does then have increasing claim to be a big-tent party and this is all the more likely to be the case in future unless the most likely government to emerge in the next few weeks, a grand coalition between CDU/CSU and SPD, achieve some notable successes in changing/reforming Germany over the next four years. Here, history does not suggest a great likelihood of success.

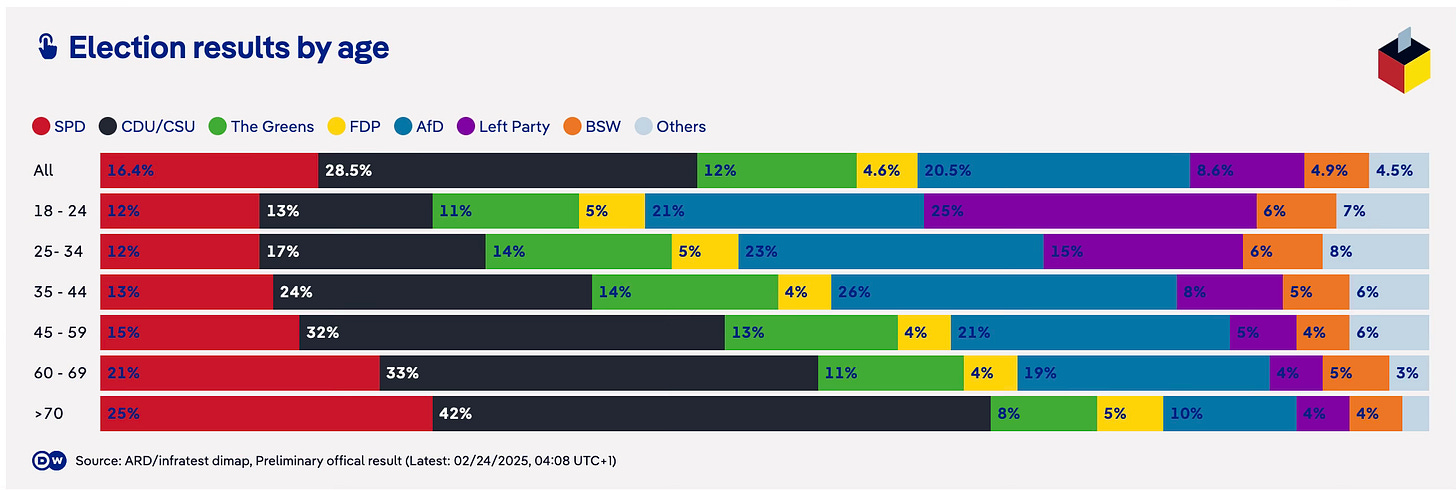

First, the AfD is not only gaining ground in the west but also among younger voters: it came second with 21% among 16-24 year-olds, just behind the Left party (Die Linke) on 25%, first among 25-34 year-olds with 23% and among 25-44 year-olds with 26%. This is a long way from the old far-right political force, ex-Waffen SS Franz Schönhuber's Die Republikaner, with their base among disgruntled cops and the like.

Second, the three recent grand coalitions headed by Angela Merkel (2005-09, 2013-17 and 2018-2021) are not notable for economic reform or innovation but, rather, sluggish growth and business decline plus, in many eyes, unmanaged immigration. The AfD and the Left together have 216 seats or just over a blocking minority (210 out of 630 seats) that can prevent constitutional reform, including the infamous debt brake that has been used to hold back long overdue investment in modernising infrastructure. (Merz, interestingly enough, is reportedly trying to remove the brake before the new Bundestag begins its first session...)

Analysts are sceptical that Merz, even with his background as a corporate lawyer and banker, can solve the deep-seated issues facing the German economy and, of course, he has to deal with a radically changed geopolitical/geoeconomic order under Trump - tariffs, tilt to Russia, evident disdain for Europe...Analogue Germany is unfit for the digital age and is becoming an innovation backwater.

All this suggests that, while the next four years offer the prospect of some change in Germany and, notably, in the EU under new leadership, we should not hold our breaths. The AfD Kanzlerkandidatin, Alice Weidel, defiantly spoke of winning in 2029 on Sunday night. In a politically fragmented and economically stagnant landscape she is in danger of being proven right unless the mainstream centre parties prove capable of governing with unusual élan.